Short summary of the plot:

During the Edo Period of Japanese history, predominantly a

time of peace, a vassal of a local clan (Isaburo Sasahara) is ordered to take

his lord's ex-mistress (Lady Ichi) as his son's (Yogoro Sasahara) wife. Lady

Ichi fell from her lover's graces when she struck him in a fit of anger. At

first Isaburo remains skeptical. His marriage has been a hapless one for 20

years, and naturally he want's his son to have a better fate. Nevertheless,

they're forced to accept, and through an incredible stroke of luck, Ichi turns

out to be an excellent wife for Yogoro. They have a daughter together, Tomi,

and Isaburo couldn't be happier for his son.

A few years later, the lord's oldest child (and primary

heir) dies, and as such Lady Ichi's son (whom she had when she was still the

lord's concubine) becomes the primary heir. The heir's mother cannot be married

to a vassal, and soon an order comes for her to return to the lord's household.

This time, Isaburo and Yogoro refuse to obey the lord's order, resulting in a

rebellion against their clan and their lord.

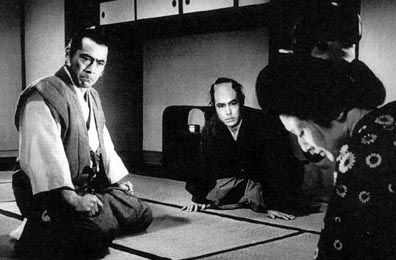

Samurai Rebellion is a multilayered film, and as far as

Samurai films go, an uncharacteristic one

(at least if you're accustomed to Kurosawa films). Not unlike Kobayashi's previous film,

Hara-kiri, Rebellion attacks the rigid social structure of the time, under

which its characters feel imprisoned and inauthentic. Compared to its predecessor,

Rebellion is more personal, and as such, more blatant. "Father is father;

I am me." Lady Ichi utters when confronted with the consequences of her

actions. Her choice is a reasonable one, her actions justified, but the clan

won't have it.

To understand the essence of the film we must first

examine its conflicts - and Kobayashi wastes no time in telling us what they

are. Isaburo and his friend Tatewaki express their dissatisfaction with the

current state of affairs. In times of peace a samurai's life is but a boring

one. Martial arts are a waste of time,

and their practitioners may, at best, put them to use by cutting straw dummies to demonstrate the quality of a sword. Their existence is

dominated by their mundane family lives, and convoluted political plots. For

example, Isaburo confesses that he married into his wife's family (and took her

name) only so he may advance in rank and make a career for himself. Otherwise

he is unhappy, and we see plenty of examples of this. When the time comes for

his son to choose a wife, he wants a better fate for him. The fact that the

wife forced on them turns out to be a good one, is pure luck.

For most of the duration of the story the main characters

hardly exercise their free will. We get the impression that they never have a

choice in the unfolding of their lives, but instead serve as cogs in the

machine that was Japanese society. That is until the introduction of Lady Ichi.

I find the reactions towards her character interesting.

Everyone, without exception, condemns her for attacking their lord, even if

later they come to understand her actions. Perhaps the contrast between her and

the Sasahara family is not obvious to them. She's not trapped under the heavy

veil of social norms ; on the contrary, she acted freely and authentically on what

she perceived to be a great injustice. It isn't until much later that Isaburo

understands this fact. And the conclusion is inevitable. Isaburo strips his

home from all furniture (this being an obvious symbolic gesture) and declares

he's never felt more alive than now.

The film ends with a series of action packed scenes with

Isaburo cutting and slashing the lord's henchmen as he tries to make his escape

to the capital. He is eventually overtaken by rifles, but only after he's

killed most of the other samurai. Soaked in a bath of his own blood, he directs

his last words to Tomi, who's taken home by the nurse. The film's ending is

both positive and negative, characteristic of most Kobayashi films. The optimism

may be hard to grasp at first, but if we step back for a moment we see that,

regardless of the tragedy, the characters died making their own choices,

crafting their own destinies. That's perhaps the most they could have asked

for.

Comments

Post a Comment